This message needs to be spread far and wide:

This message needs to be spread far and wide:

People in the United States have the right to videotape the actions of government employees in public spaces.

As I noted in an earlier post, the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania has published a useful summary of the rights of citizens to record interactions with government employees, and in particular, the police.

Taking photographs and videos of things that are plainly visible from public spaces is your constitutional right. That includes federal buildings, transportation facilities, and police and other government officials carrying out their duties. … Police should not order you to stop taking pictures or video. Under no circumstances should they demand that you delete your photographs or video.

Just today, there were two more reports of law enforcement officials demonstrating open hostility to citizen video recording. In Boston, a sergeant named Harry Staines is under investigation for telling a man that he could not record the police while they interviewed a 14-year-old about a realistic-looking fake gun. Boston Police Commissioner William Evans has acknowledged that Sergeant Staines acted inappropriately and apologized, saying that “Everyone is allowed to videotape. It’s their constitutional right to do it.”

More troubling is the arrest at gunpoint of Kevin Moore, one of two people who recorded video of the arrest of Freddie Gray last week. Moore and two members of the organization WeCopwatch were arrested on Thursday and held on unspecified charges. Moore was released after two hours or so, but his companions remain in custody.

Moore believes that he was singled out for harassment, despite cooperating with the police and turning over his video, and says that his treatment is similar to what happened to Ramsey Orta, the man who filmed the death of Eric Garner in July 2014. Just two weeks after he shot the video, Orta was arrested and jailed on weapons charges. A short time later, prosecutors added a drug charge. Orta was held in Riker’s Island prison in lieu of $100,000 bail until earlier this month, when friends and family raised enough money on the crowdfunding site GoFundMe to pay a bail bondsman and fees for his release.

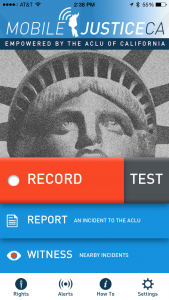

As Jon Wiener at The Nation pointed out, when it comes to recording the interactions of police with the public, there’s an app for that. The ACLU in California has just released “Mobile Justice CA,” an app that provides one-button recording and archiving of cellphone videos.

When an app user clicks the big, bright red “Record” button, the app simultaneously sends a copy of what’s being recorded to the ACLU. When the stop button is pressed, the user is given a chance to “Report” the incident by supplying various pieces of information. Even if the user does not have a chance to report what is going on, a copy of the video is preserved in case it is needed for some purpose down the road.

As the Pennsylvania ACLU notes, a police officer can request that an individual stop recording if the act of recording is interfering with the police officer’s ability to do his or her job. That helps explain why the Texas legislature is considering new legislation that would make it a misdemeanor for a private citizen to get within 25 feet of a police officer when making a video recording. A handful of other states are also considering legislation to clarify what constitutes “interference.”