[Update 2017-05-23]: On Tuesday, May 23, the Federal Communications Commission issued a statement that it will not take any action against Stephen Colbert for a sexually-explicit joke [see below] that he made about Donald Trump on the May 1 episode of his show, “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.”

[Update 2017-05-23]: On Tuesday, May 23, the Federal Communications Commission issued a statement that it will not take any action against Stephen Colbert for a sexually-explicit joke [see below] that he made about Donald Trump on the May 1 episode of his show, “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.”

According to Variety, which was the first to report on the FCC’s statement, the critical portion of the statement read as follows:

Consistent with standard operating procedure, the FCC’s Enforcement Bureau has reviewed the complaints and the material that was the subject of these complaints. The Bureau has concluded that there was nothing actionable under the FCC’s rules.

As my original post makes clear, I believe that the FCC has reached the correct decision. The only improvement, in my opinion, would be for the FCC to wash its hands of the cultural decency battle altogether.

[Original Post]: A little over twelve years ago, as the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show drew to a close, Justin Timberlake reached around the front of his duet partner Janet Jackson and dramatically popped off a piece of her leather bustier. The only thing Ms. Jackson was wearing underneath that flap of leather was a sunburst-shaped nipple piercing, a jewelry choice that suggested to many observers (and obsessive re-observers) that the eye-opening ending was both planned and choreographed.

The very next morning, the then-chair of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Michael Powell, made the rounds of the morning talk shows and promised an aggressive investigation into Jackson’s half-second of on-air nudity. Seven months later, the FCC fined CBS and its parent company Viacom $550,000 for the incident. Viacom appealed the fine and after the case bounced around the courts for nearly 8 years, the U.S. Supreme Court eventually upheld a 3rd Circuit ruling that the incident constituted “fleeting indecency” and that the FCC’s fine was “arbitrary and capricious.”

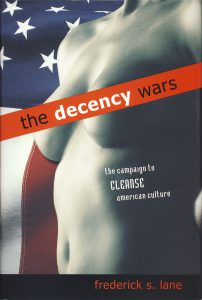

My book The Decency Wars: The Campaign to Cleanse American Culture (Prometheus Books 2006) used the Jackson-Timberlake incident as a starting place for understanding the history of the battles over the cultural decency in the United States. Thanks in part to the subject matter and in part to the provocative cover, it led to an appearance in August 2006 on “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart” [clip below].

The role of the FCC in regulating on-air speech is in the news once again, thanks to a scathing monologue by “Late Show” host Stephen Colbert on Monday, May 1. It was a savage summary of President Trump and his first 100 days in office that concluded with this remarkable statement: “You talk like a sign-language gorilla that got hit in the head. In fact, the only thing your mouth is good for is being Vladimir Putin’s c*ck holster.”

In a regrettably rare instance of national unity, Colbert’s disparaging allusion to a post-Cold War gay sex act managed to infuriate some viewers on both the right and the left ends of the political spectrum. Current FCC Chairman Ajit Pai did not react quite as quickly as his predecessor, but by the end of the week, was telling reporters that the FCC would “take the appropriate action.”

I believe that the most “appropriate action” the FCC can take is none at all. In fact, I contend that it is long past time for the FCC to get out of the business of speech regulation altogether.

The Origins of FCC Speech Regulation

Normally, the government is prevented by the First Amendment from imposing any limits on free speech unless the law or regulation in question can survive “strict scrutiny” by the federal courts. Under that standard, the government must prove that it has a compelling interest in limiting the speech and that the law or regulation is “narrowly tailored” to achieve the desired outcome with as little curtailment of First Amendment rights as possible. That challenging standard protects the bulk of American speech from government interference, from street corners to books to the wild, wild West of the Internet. The rules for on-air speech, however, are different.

Ninety years ago, Congress was faced by a growing cacophony of radio broadcasts. Recognizing that radio frequencies were a limited resource, Congress adopted the 1927 Radio Act. The law created a Federal Radio Commission (the FCC’s predecessor) to manage the airwaves by issuing licenses that governed a station’s frequency, power, hours of operation, etc. But Congress also included language that authorized the FRC to suspend the license of any operator that transmitted “profane or obscene words or language.” These prohibitions were inspired by similar language in the Comstock Act, an 1873 law that threatened imprisonment at hard labor for up to 10 years to anyone mailing “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” materials, or anything “indecent or immoral.” The evangelical origins of the law can be seen in the fact that those broad terms applied not only to sexual speech but also to any information about birth control or abortion.

Obviously, things have changed a bit since purity crusader Anthony Comstock was hired by the New York YMCA to lobby for the anti-obscenity legislation that bears his name. According to its own current regulations, the FCC does not take any action against “indecent” on-air content during its so-called “safe harbor” of 10pm and 6am, on the theory that children are less likely to be watching. However, the FCC retains the ability to punish indecency at all other times and sternly warns that “[i]t is a violation of federal law to air obscene programming at any time.”

Colbert’s Joke Was in Bad Taste but Not Obscene

Since the “Late Show” airs at 11:30pm, the FCC will be assessing whether Colbert’s comments were obscene. There is no statutory or regulatory definition of “obscene.” Instead, in determining whether on-air content is “obscene,” the FCC applies the three-part legal test announced by the U.S. Supreme Court in Miller v. California (1973). The first prong of that test asks a factfinder to determine whether “the average person, applying contemporary community standards” would conclude that the work, “taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest[.]”

It is doubtful that anyone’s prurient interest was stirred by Colbert’s comment. The more significant problem, however, is determining which “contemporary community standards” the FCC should apply in its assessment. Usually, it is the community in which a book is sold or a DVD is rented that supplies the relevant contemporary standards. But the “Late Show” is a nationally-broadcast program, the content of which is available in virtually every community in the country. Logically, the only applicable “community” for the FCC to consider is the nation as a whole. In making its assessment, the FCC should take into account all of the factors that contribute to our contemporary standards, from the coverage of the Monica Lewinsky scandal to Anthony Weiner to Trump’s Access Hollywood comments. Fold in some time surfing the Internet and it is hard to argue Colbert’s comments violate our contemporary national community standards.

In its FAQ on indecency, the FCC tries to get around this problem by looking at “contemporary community standards for the broadcast medium,” i.e., broadcast television. But that, of course, is not what the Miller test says. More importantly, it is a circular argument: The contemporary community standards for a particular broadcast medium are determined by what the FCC will allow on that medium. When regulation by the government determines what the government can regulate, that is a clear sign of a constitutional problem.

The “Community Standard” for Children Has Changed As Well

Even if Colbert’s broadcast occurred outside of the “safe harbor,” I do not think that the FCC should take any action. Media censors and decency activists have long relied on the need to protect the young and the innocent — ah, the children, the children! — from the harm of premature exposure to various types of speech (ranging from George Carlin’s brilliant but scatalogical humor to adult video). But the rise of the Internet and the widespread use of smartphones by younger and younger children forces us to consider whether the purported benefits of FCC censorship still outweighs the potential harm to our First Amendment freedoms.

I believe the U.S. government, acting through the FCC, could demonstrate a compelling interest in protecting children by regulating on-air speech only so long as it was the chief gatekeeper for that speech. When the bulk of commercial speech traveled over the airwaves, it made sense for the government to act as a partner with parents in placing reasonable regulations on what could be aired at different hours of the day. However, the government’s monopoly on the distribution of “broadcast” content (i.e., speech sent to millions of people at once) began to crumble with widespread subscription to cable television in the 1980s. A decade later, when the World Wide Web burst onto the scene, the broadcasting of content exploded and the government’s regulatory monopoly completely dissipated.

No current parent should have any illusions about their child’s ready access to broadcast content, regardless of the time at which it was original aired. Every late-night monologue and sketch can be watched on any Internet-connected device within hours of its release and there is no practical method for limiting the distribution of such content to individuals above a certain age. Moreover, parents have played a central role in providing their children with access to all of that of content (and more) by subscribing to cable television, by providing them with smartphones, and increasingly, by installing devices capable of streaming multiple online sources of content. (Have you seen what is available on Netflix? Your teens undoutedly have.)

After nearly a century of government oversight, I believe it is time to apply strict scrutiny to the government’s argument that the FCC’s regulatory authority is still “narrowly tailored” to the goal of protecting children. In light of the immense social and technological changes that have taken place over the last two decades, the only reasonable answer is “no.” To conclude otherwise is to run the risk of reducing all broadcast speech to the level of the most impressionable child with access to the Internet. That is a standard the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently rejected.

The Marketplace, Not the Government, Should Determine Colbert’s Punishment (If Any)

The logical conclusion is for the FCC to get out of the business of speech regulation altogether. For much of its history, the FCC’s regulation of speech was predicated in large part on the fact that only the U.S. government could effectively police the content on the airwaves. What recourse, after all, could individual citizens or parents have against misbehaving broadcasters? But that is no longer true.

As the recent departure of Bill O’Reilly from Fox demonstrates, consumers and citizens now have powerful social media tools to punish broadcasters and their employees who violate contemporary social norms. Such activism is in fact a real-time manifestation of the “contemporary community standard” enunciated by the Supreme Court in 1973, but now made manifest on a national scale through the use of digital technology. And in fact, thousands of people did express their disapproval of Colbert’s language on outlets like Twitter and Facebook. While not reaching the white-hot heat that chased advertisers from “The O’Reilly Factor,” the outcry was still large enough that Colbert it necessary to address the controversy and offer a tepid apology.

Ultimately, it should be up to the public, not the government, to determine whether Colbert went too far in his monologue or not far enough in his response.

My Appearance on “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart”

| The Daily Show | Mon – Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Frederick Lane | ||||

|

||||