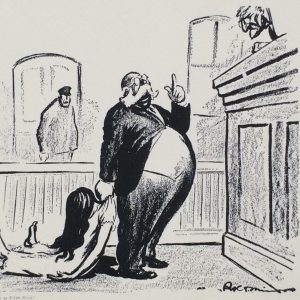

“Your Honor, This Woman Gave Birth to a Naked Child!” Robert Minor, Cartoon of Anthony Comstock (1915)

By Dr. Amy Werbel

Author of the forthcoming book Lust on Trial: American Art, Law, and Culture During the Reign of Anthony Comstock [Columbia University Press, 2018]

A new word has entered common parlance and it bodes well for the future of democracy: Trumpism. The tendency of Donald Trump to run his campaign and his administration as a one-man show has organically promoted his family name to the status of an increasingly pejorative noun. The term Trumpism encompasses everything he has done, said, and represented, as well as everything that has been imputed to him. Extravagant wealth, bigotry, selfish business practices, alpha male crudeness, authoritarian and alt-right political positions, lack of discipline and preparation, and a willingness to say absolutely anything to “win” already accrue to the term. Trumpism surely will gain dimension in the years to come as our new President adds actual power to his media-fueled bluster.

The phenomenon of a family name turning into a heavily loaded noun is not entirely new, but it is particular. The terms Clintonism and Clinton World represent a number of individuals in private and public sectors, along with their policy platforms, political strategies, and relationships. Trumpism, however, much more closely resembles the phenomenon of “Comstockery” a century ago.

In 1905, the British playwright George Bernard Shaw coined the term Comstockery as a mocking complaint against the censorship of his play Mrs. Warren’s Profession. “Comstockery,” he wrote, “is the world’s standing joke at the expense of the United States.” Shaw was referring to Anthony Comstock, who rose to power in 1873 as an Inspector for the U.S. Post Office Department, and also as Secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Comstock considered himself to be the nation’s first federally appointed censor; by the time Shaw decried Comstockery, Comstock the man had supervised the destruction of truly massive quantities of newspapers, books, pictures, condoms, etc., as well as the incarceration of thousands of alleged producers and distributors of what he considered vice.

Although this dubious accomplishment suggests social and political victories for Comstockery, and therefore potentially for Trumpism, the unintended consequences of his actions far outpaced those Comstock anticipated. After his narcissistic brand of misrule was named in 1905, the aging censor became a visual embodiment of foolish prudishness, unconstitutional police and courtroom tactics, evangelical intolerance, government overreach, and unequal application of the law. As the literal and visual embodiment of all these perils to democracy, Anthony Comstock became a singular target for a wide variety of detractors who previously didn’t like each other very much.

A year after the term Comstockery entered common parlance in 1906, Comstock raided the Art Students League of New York in a case that was widely reported. A New York Times reporter found the young art student Everett Shinn organizing his classmates at the League: “Boys, you know what to do with him. Cartoon him until the cows come home . . . Get at him! Get at him!” Another essayist writing a month later summarized that the word Comstockery had taken on “a new and additional potency not dissimilar from that which a red flag exerts upon a herd of long-horned bovines.”

The odd bedfellows who gathered to oppose Comstockery didn’t agree on much beyond the need for its defeat. They included writers, artists, journalists, theater managers and publishers who fought for freedom of expression and professional self-governance. Birth control advocates including Margaret Sanger and Emma Goldman fiercely disagreed about how to pursue their goals, but they raised money for each other’s defense in common cause. Attorneys including Theodore Schroeder and Clarence Darrow rallied to form organizations (precursors to the American Civil Liberties Union) that were dedicated to honing the skills necessary to defend clients charged with obscenity violations. Together, these disparate and fractious individuals and organizations locked arms, raised money, won court cases, changed cultural attitudes, and ultimately laid the groundwork for modern free speech rights. Americans for the most part refused to be subjugated.

We have ample evidence already that America still is filled with brilliant artists, writers, performers and thinkers, ardent libertarians, and plucky and persistent lawyers who are organizing rapidly. As the popular vote in this election attests, we are a large, diverse nation that still mostly believes in pluralism and the rule of law. Once again, we have the opportunity to run a dangerous matador out of our democratic arena using all our intellect, creativity, skills, and resources. History offers a lesson on what we need to do first: look beyond our differences and join in common cause. We have our man, now get at him.

About the Author

Dr. Amy Werbel is an Associate Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology and a member of the History of Art Department. She is the author of two books: Thomas Eakins: Art, Medicine, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007), and Lessons from China: America in the Hearts and Minds of the World’s Most Important Rising Generation (Self-published. Printed by CreateSpace, 2013). Her latest book, Lust on Trial: American Art, Law, and Culture during the Reign of Anthony Comstock (New York: Columbia University Press, forthcoming), will be published in 2018.Lust on Trial: American Art, Law, and Culture During the Reign of Anthony Comstock