Sometime during the middle of the 2013-2014 school year, Kearney Day, a 20-year-old teacher’s aid in the Allen Independent School District, used the Kik messaging app to start chatting with an unnamed 16-year-old student.

In April 2014, the student told members of the Allen High School administration that she and Day were in a relationship. During an interview with the Allen police, the student said that the relationship began shortly after she told Day that she was having trouble at home. After communicating for a period of time on Kik, Day spent the night of Valentine’s Day with the student at her house (her mother was out of town). The student showed police a photo of Day in the student’s bed but initially told the police that there had been no sexual contact.

A short time later, the student approached the school’s resource officer and told her that there was more to the story. She said that she and Day engaged in sexual activity several times during Day’s visit and described several tattoos on Day’s body. She told the officer that she originally failed to tell the complete story out of a desire to protect Day.

During their investigation, the police were able to recover a number of the Kik messages exchanged by the two, including one that made it perfectly clear that Day understood the risks of what was taking place:

I’m about to lose my goddamn job over this… Keep your mouth shut about me. So much for being able to trust you to in the beginning idek [sic] if ill [sic] be able to talk to you in the hallway now cause someone’s spying on my [expletive].

Day was arrested on May 8, 2014, and charged with nine criminal counts, including improper relationship between an educator and a student, sexual assault on a child, and indecency with a child sexual contact. Nearly two years later, in late March 2016, Day agreed to plead guilty to a single count of improper relationship, which is a second-degree felony in Texas. The remaining counts were dismissed by the prosecutor.

The court sentenced Day to four years deferred adjudicated probation and fined her $500. The court also said that she cannot have any unsupervised contact with children and must perform 120 hours of community service.

Reflections and Discussion Points

The Slope to Misconduct Today Is Much Steeper and Slippier: As is so often the case, the improper relationship between Day and her student appears to have arisen out the educator’s legitimate concern for a student having a difficult time at home. Given the amount of time that students spend with educators and the inherent closeness of the student-teacher relationship, it should not be surprising that students turn to their teachers for advice and consolation. It is also not surprising that under the right circumstances, otherwise appropriate friendliness and even affection turns romantic and/or sexual.

(I am setting aside for the moment the cases in which a teacher is not so much empathetic as predatory, and actively seeks out a hurt or wounded student on which to prey. That could be the case here, but for the purposes of this discussion, I am assuming it is not.)

What needs to be reiterated time and again are the myriad ways in which digital technology can accelerate the transition from empathetic educator to sexual assaulter. The single biggest factor is the ability of adults to hold unmediated and unmoderated conversations with children at all hours of the day and night using a seemingly endless number of communication tools. There are hundreds, if not thousands of alternatives to POT (plain old texting), and the choices are only going to continue to multiply.

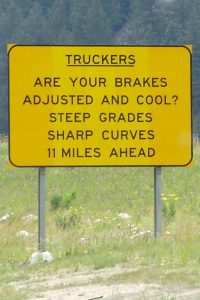

The reality is that school districts and administrators cannot keep ahead of the technological curve. Inevitably, the digital roads that teachers travel with their students will continue to grow steeper and slippier.But as every driver knows, the keys to surviving difficult road conditions are anticipation and preparation: You need to be able to see potential hazards and you need to be prepared to handle them. For motorists, that means knowing the route, paying attention to warning signs, and making sure the car has all the appropriate equipment (tire chains or studs, for instance) to stay on the straight-and-narrow.

For educators, that means education and ethics. It is categorically unfair for school districts and administrators to expect their teachers to successfully negotiate the twists and turns of technological change without regular and thorough education about the risks they face. But that’s not enough. Even teachers who clearly see the dangers they face can still slide down the slope if they are not adequately prepared. I believe that the best way to increase the coefficient of friction for educators is a comprehensive program of educator ethics, from pre-certification training to ongoing professional development.

The Need for App Self-Audits: Developing and implementing a profession-wide program of pre-certification ethics training and ongoing professional development obviously is beyond the capability of any single district. But there are various less comprehensive steps that individual districts can take to help their educators think about these issues and spark conversations about the risks that might arise.

One exercise that should be done at least once or twice a year is to ask educators to answer two questions: 1) What communication apps are installed on their smartphone and 2) What communication apps (or social media sites) have students used to communicate with them?

The first question might be more difficult than it looks. It is easy enough to identify and list the iOS and Android apps that are clearly designed for communication (WhatsApp, Kik, WeChat, Skype, Twitter, etc.), but many apps that are designed for other specific purposes can also be used for communication. For instance, Instagram and Snapchat were initially developed for posting and sharing photos, but both services have added their own messaging components (similar to Facebook Messenger). The majority of contemporary multi-player games come equipped with chat or voice-over-IP (VOIP) capabilities that allow people to communicate in real time. Even some so-called “anonymous” apps (like Whisper) can be used for one-to-one communication.

The second question is more straightforward: educators simply need to list the various communication tools that students have used to contact them. It may be surprising to many educators (and to administrators) just how many different ways students try to reach out to their teachers.

Every school district should have in place policies that address the time, place, and manner of digital communication between teachers and students. Teachers should be discouraged, for instance, from communicating one-on-one with students after a certain time in the evening. Ideally, all student-teacher digital communications should be archived and available for analysis by administrators and/or parents. Where that is not possible (for instance, with text messages or other types of messaging), it should be standard practice for educators to include another adult — an administrator, a colleague, or the student’s parent(s) — in the conversation. As with ethical training, communication transparency is another excellent source of friction to make navigating these slippery slopes a little easier.